The Suwo’di organization and UNESCO, Costa Rica, hosted a webinar on Citizen Science on 10th November, to bring together local experts and enthusiasts that are working on this theme. Isabella Cubillo, the new Communications Officer from Human Right 2 Water, joined in with a presentation on a social engagement app that can be used for local water forums to monitor water quality.

What is Citizen Science?

First of all, in definition, Citizen Science can be considered the initiative of taking scientific knowledge back to the communities and to their actions. In other words, its purpose is to have communities participate and benefit from scientific knowledge through their experience. Consequently, this can promote their participation in projects and initiatives that contribute to research and development within a specific area.

Challenges for Citizen Science

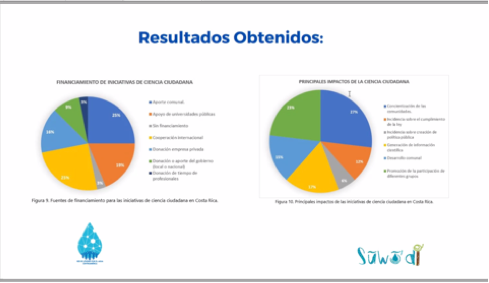

In the case of Costa Rica, where the Suwo’di organization carried out a diagnostic to identify initiatives for water conservation, the main problem identified was the lack of knowledge and inclusion of citizen science within public policies and initiatives. Additionally, when Citizen Science is included, it is considered as the sharing of scientific knowledge with the communities instead of including them and having them participate in these processes. The reasons behind this problem are the lack of funding, lack of participation/initiative on behalf of the communities, and lack of training to lead these types of programs.

Which Citizen Science initiatives are being developed and why have they been successful?

One of the myths that stops the communities from getting involved is the belief that freshwater sources and rivers cannot be restored. The organization, HIDROCEC, is one of the few organizations that has promoted the Citizen Observatory of Water for the Liberia River in the province of Guanacaste. This Observatory went from conventional monitoring to citizen monitoring. They aim to not only involve people, but in addition, educate them regarding water conservation. The participation and leadership done by the youth has been the key to develop activities, both in-person and online, that help communities to take care of the river and to promote the conservation of water.

The organization ANAI has also been involved in the zone of Talamanca with the goal of monitoring rivers with the help of the communities. Working with the communities and not for the communities is essential as they are the ones that live in the area and make decisions; therefore, the work being done should reflect this in these processes. Additionally, they have also tried to involve schools through environmental education programs that allow the participation of children and young adults in the monitoring of the rivers. These types of institutional alliances have not only allowed an increase in local participation, but also to increase the environmental awareness of all generations, especially those in whose hands lie the future of the community.

Then, the organization Nicoya Península WaterKeep also has promoted conservation of rivers to create a more environmentally aware culture that protects and reports any misconduct that pollutes rivers and freshwater sources. This has been a collaborative work between the communities, municipalities, and a group of engineering experts that has allowed the development of water quality analysis, clean-up days, collective report on civilian misconduct, physicochemical analysis, and more. The intervention which the experts can provide has allowed to have a bigger impact thanks to the technical knowledge that they can add throughout the development of the projects.

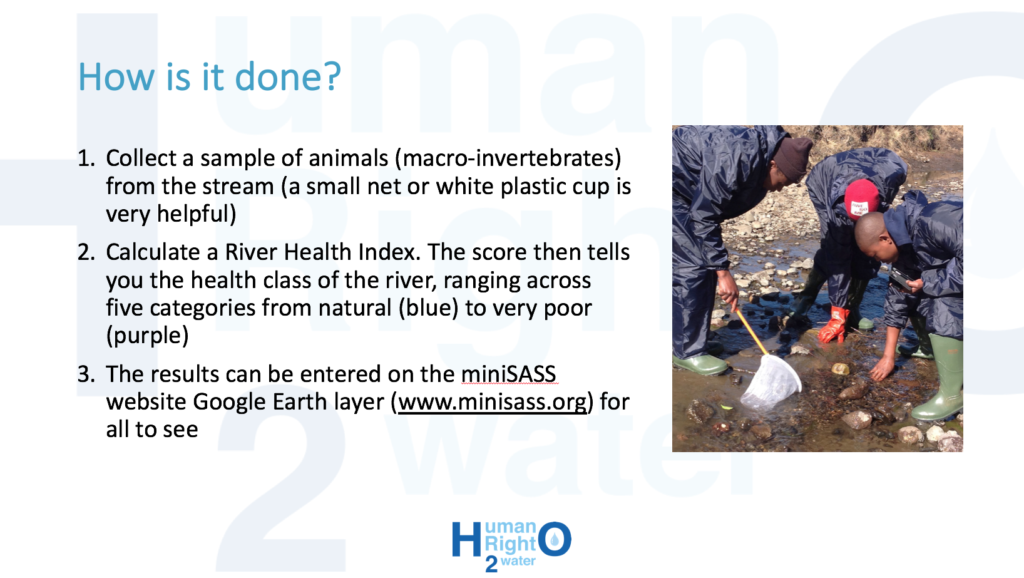

Lastly, Isabella presented the Social Engagement app called the Stream Assessment Scoring System (miniSASS) that Human Right 2 Water and the World Water Quality Alliance are promoting. This tool is not only simple to use, but there is also no cost involved when using it. This allows organizations with smaller budgets to include their communities in water conservation projects. Additionally, it allows to monitor the water quality of rivers through space and time.

The key to these successes has been the collaboration between groups: the academy, the government, the experts, and the communities. Involving academic units has allowed for all the scientific knowledge developed through research to return to the communities. This can be done through community service programs within universities that are looking for programs for their students. Additionally, while many experts tend to have positions in the national or local governments, these can also be found elsewhere and the implication that political rotation has on the continuity of the programs can be mitigated. Therefore, finding experts that are willing to help from inside or outside of the communities is also a strategy that allows to better value and promote initiatives effectively. None of this is possible without the effort of the communities, these are necessary so that the work done by organizations is sustainable and lasting.

Panelists:

- Dr. Christian Golcher from HIDROCEC and the Water Citizen Observatory of the River Liberia

- Maribel Marla Herrera from ANAI

- Luis Gomez from Nicoya Península Waterkeeper

- Isabella Cubillo from Human Right 2 Water

- Kenneth Alfaro from Suwo’di

Facilitators:

- UNESCO

- Suwo’di

Opening remarks:

- Kenneth Alfaro Alvarado, Project Manager from Suwo’di

Discussion

- Dr. Christian Golcher from HIDROCEC

- Maribel Marla Herrera from ANAI

- Luis Gomez from Nicoya Península Waterkeeper

- Dalys Govira.

Closing remarks:

- Kenneth Alfaro Alvarado, Project Manager from Suwo’di